How I Built This Thing (Part 1): Designing a 3D Engine the ZX Spectrum Was Never Meant to Run

There is no single trick that makes World of Spells fast.

No magical routine, no one golden optimization, no secret Z80 opcode.

What exists instead is a stack of optimizations, each one pushing the machine a little further until the whole thing crosses a threshold where 3D movement, 80 FPS corridors, moving objects and mirrors all become possible.

In this first article I want to show something that’s easy to miss when looking at the finished game:

this engine is not built — it’s refined. Every subsystem in World of Spells went through up to six levels of optimization, with most functions rewritten four times before they were acceptable.

I started with a simple prototype written in C. It ran, but the framerate was somewhere between “slide show” and “loading bar.” From there the process began:

Six Stages of Optimization (OL1 → OL6)

(OL1) Working C prototype.

It proves the idea but is too slow to keep.

(OL2) First rewrite in assembly.

Still friendly, still readable, but at least 10× faster.

(OL3) Algorithm-level experimentation.

Change data layouts, remove multiplications, realign tables, rewrite interfaces.

This is where many functions get thrown out and rebuilt from scratch.

(OL4) Final optimization pass.

Count cycles with z88dk “ticks,” compare real-world FPS, unroll loops, move stack pointer for faster memory access, reorganize pages, rewrite again.

(OL5) No more improvements found — for now.

The routine is optimal for the chosen test scenario.

Different scene? Maybe new tricks appear, maybe not.

(OL6) Absolute limit reached.

Past OL6, every attempted optimization makes code slower.

Most of the core engine — especially the raycaster and renderers — sits between OL5 and OL6. Getting there takes days or weeks for each subsystem.

A Game Built From Bottlenecks

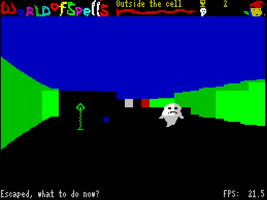

From the outside the game looks simple: 32 rays, 32 columns, ghosts, fireballs, wands, treasures.

Inside, each subsystem fights ferociously for cycles.

-

Raycasting needed to complete in ~850 cycles per column on a long corridor test scene.

-

Object movement must handle up to 17 dynamic entities in a stable way.

-

Rendering has to touch the framebuffer only when needed.

-

Sorting must be fast enough to run every frame, but accurate enough to prevent overlapping objects.

-

Math must avoid real trig entirely — replaced with hand-built LUTs.

The design philosophy quickly became:

Do nothing unless absolutely unavoidable.

And when you must do something, do it the cheapest possible way.

Tables, Tables, Tables

On a machine without multiplication hardware, trigonometry, or fast memory access, the only way out is precomputation. I ended up using:

-

64-byte sine table

-

256-byte atan table

-

256-byte log2 table

-

256-byte exp2 table

-

33-byte tangent table

-

33-word log(sin) table

-

33-byte log(cos) table

-

Various raycasting helpers (min/max, distance tricks)

-

1024-byte high-precision tangent table (init-time, optional)

Almost all of these tables were generated with small Octave scripts — because manually computing them would be a new level of masochism even for ZX Spectrum enthusiasts.

Angles? Stored in 1 byte (0–255 → full circle).

Distance? Logarithms instead of multiplication.

Perspective? Exponentials instead of division.

The pattern repeats:

Use the lowest-cost operation the hardware gives you, then work backwards to represent the math in that domain.

Everything Is Self-Modifying

If you want speed on Z80, you eventually end up modifying your own instructions. The raycaster, renderer, sprite blitter — they all have variants that rewrite small pieces of themselves. This saves registers and avoids expensive address recalculations.

It’s not pretty, but it’s fast.

Combined with stack-pointer tricks, careful page alignment, and loop unrolling, this is how the core kernels reach OL6.

The Heart of the Beast: A Minimal Raycaster

The raycaster is split into three specialized kernels:

-

X-optimized

-

Y-optimized

-

A fallback kernel for special cases (objects, edge conditions)

It casts only 32 rays, but each ray is extremely cheap. Instead of real geometry math, each ray:

-

Walks a 16×16 map (fits perfectly in 8-bit addressing)

-

Chooses X or Y distance to avoid multiplications

-

Uses log/exp tables for height computation

-

Reuses angle correction tables

-

Clips only what is necessary

-

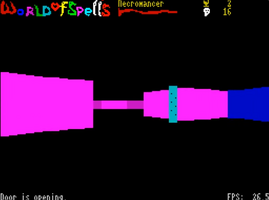

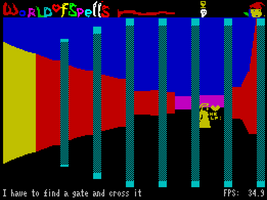

Detects mirror hits (reflection!), cage patterns, doors and “tall blocks”

At benchmark scenes it can reach ~128 FPS with rendering disabled.

Mirrors are my favorite part. On a ZX Spectrum. In real time. In a raycaster.

It’s absurd — but it works.

Rendering: Do Less, Draw Less

The basic renderer is column-based. It has multiple kernels, each optimized for a specific column height so the CPU doesn’t spend time branching inside a loop.

It also uses adaptive refresh:

-

If a column did not change → do nothing.

-

If height changed slightly → update only edges.

-

If only color changed → update only color.

-

If pattern should appear → paint only the required 8×8 zone.

This “paint nothing unless forced” strategy saves thousands of cycles per frame.

Later in the series I will cover:

-

the interpolating renderer

-

sprite scaling + caching

-

object sorting using partial bubble passes

-

the movement simulation

-

dynamic lighting

-

memory layout decisions

-

tools (map editor, sprite editor, Octave scripts)

-

gameplay scripting inside strict engine constraints

For now, it’s enough to say:

The engine is not fast by accident — it’s fast because every single instruction was questioned.

What This Project Really Is

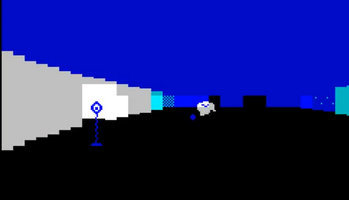

People often compare World of Spells to early PC games like Hovertank 3D or Wolfenstein 3D.

The truth is both funnier and harsher:

It’s what Wolfenstein might have looked like

if id Software had been forced to write it for a ZX Spectrum.

No texture mapping.

No multiplication.

Barely any memory.

LUTs everywhere.

And yet… mirrors, doors, variable wall heights, reflections, dynamic lighting, fireballs bouncing off shiny surfaces.

All of this on hardware that was designed for BASIC games and homework programs.

This is not an engine built with modern convenience.

This is an engine built by eliminating everything the hardware hates — until only speed remains.

Files

Get World of Spells

World of Spells

FPS on ZX Spectrum 48k

| Status | Released |

| Author | jtpl |

| Genre | Action, Adventure |

| Tags | 3D, Doom, Exploration, Fantasy, Fast-Paced, First-Person, No AI, Sprites, ZX Spectrum |

| Languages | English |

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.